The government wins on tone but falls short on putting constitutional obligations to First Nations up front.

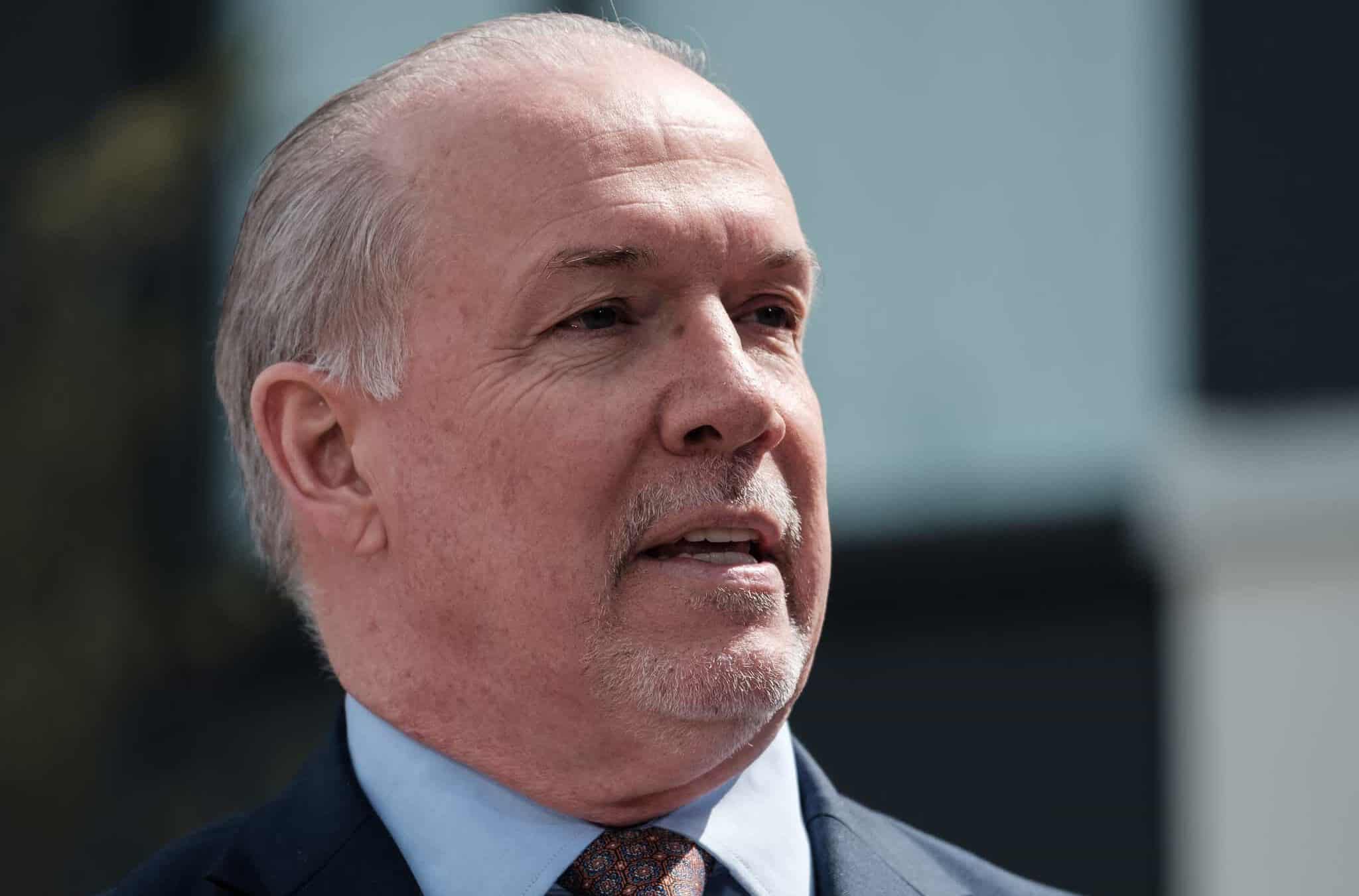

From the outraged hyperbole frothing from the lips of pro-Kinder Morgan supporters, you would think Premier John Horgan had flipped the Queen the bird with his campaign pledge to “use all the tools in the toolbox to stop” Kinder Morgan’s controversial oil tanker-pipeline proposal.

Just as Albertans expected their political leaders to fight back when Trudeau-the-dad tried to force his National Energy Plan on them in 1980, British Columbians expect our premier to fight to protect our province from bullies from across the Rockies trying to bisect British Columbia with an unwanted pipeline to deliver toxic bitumen to Burnaby for export on oil tankers.

The blowback against Trudeau Sr. changed Canadian politics for a generation. The “West Wants In” grassroots groundswell led to the creation of the Reform party, and the subsequent merged Conservatives led to Stephen Harper’s decade in power. A comparable political shift awaits if Trudeau-the-son keeps on huffing and puffing to force an unwanted proposal on our unwilling province (and let’s not forget unwilling municipalities and First Nations — but more on that later).

The pro-Kinder Morgan arguments about paramountcy, and the rule of law consume headlines, but there has been little analysis of whether Premier Horgan and his government colleagues have been fulfilling their pledge. Are all the tools in the provincial toolbox being used? What are these tools? And how effectively are they being deployed?

The escalating war of words

Horgan and Environment Minister George Hayman both deserve top marks in the verbal squabble with Alberta and Ottawa. While Alberta Premier Rachel Notley and our New Age Prime Minister appear anxious, aggressive and increasingly desperate with their multiple threats, both of B.C.’s main spokespeople on all things Kinder Morgan have appeared unflustered, undeterred and reasonable. Horgan and Heyman may be overwhelmed on the volume of hyperbole, but on substance and tone they win hands down.

Horgan’s strong performance is welcome news to anti-pipeline warriors who have been nervous because of Horgan’s uneven resolve before he formed government. Remember back to the day, after then-NDP leader Adrian Dix’s unexpected 2013 Earth Day announcement of opposition to Kinder Morgan, when Horgan knee-capped his boss by infamously speculating that the oil port could perhaps be moved to Deltaport or Fraser Surrey Docks. Perhaps personally witnessing the devastation of the tugboat Nathan E. Stewart oil spill in Bella Bella was the epiphany that strengthened his resolve on Kinder Morgan.

“No Tankers” supporters might still wish their B.C. representatives rattled their sabres more aggressively, but remember, in politics (well, in Canadian politics), the person that convinces people that they are the most reasonable usually wins. Avoiding unnecessarily aggressive language is also smart legally as many watching the controversy believe Kinder Morgan’s endgame is not to build its pipeline, but to position itself for a massive damages claim under the investor-state provisions (Chapter 11) of NAFTA.

In the legal arena

In the Kinder Morgan legal tug-of-war, British Columbia’s decision to refer the jurisdictional question to the courts was a master stroke though concerns about the timing remain. Some legal experts believe B.C. should have waited and not reacted to Kinder Morgan’s made-up May 31 deadline to walk away from the project. Trudeau and Notley screwed up by not accepting Horgan’s offer to join in the reference.

Left on its own, B.C. can now craft the legal question any way it chooses. It will likely go something like this: is there any formulation of provincial laws whereby British Columbia can regulate the health and safety aspects of the transport of bitumen through the province?

With a broad question like that, the answer from the court is obvious: “Of course, B.C. can.” Given the Supreme Court of Canada’s recent ruling upholding New Brunswick’s right to restrict Quebec beer being transported into the province, it’s hard to imagine the court ruling against British Columbia when it comes to toxic bitumen. Remember, health and safety are clearly under provincial jurisdiction in our Constitution.

While Trudeau, Notley and other Kinder Morgan cheerleaders cite the Constitution for their claim that B.C. has no jurisdiction over interprovincial pipelines, Canadian courts have been much less categorical about paramountcy (the doctrine that federal law automatically prevails when there is a conflict between provincial and federal laws).

Despite Trudeau and Notley’s huffing and puffing, the Supreme Court has rejected the notion that jurisdiction is siloed into separate watertight compartments. Our courts have made it clear that businesses operating in federal fields must also comply with provincial laws. The Supreme Court has called this “first general constitutional principle” and said finding otherwise “would create serious uncertainty.”

Our courts have consistently ruled that related provincial and federal laws can and will overlap and coexist. In the Supreme Court of Canada’s Tsilhqot’in decision (para 148) they said: “Interjurisdictional immunity — premised on a notion that regulatory environments can be divided into watertight jurisdictional compartments — is often at odds with modern reality. Increasingly, as our society becomes more complex, effective regulation requires cooperation between interlocking federal and provincial schemes. The two levels of government possess differing tools, capacities, and expertise, and the more flexible double aspect and paramountcy doctrines are alive to this reality: under these doctrines, jurisdictional cooperation is encouraged up until the point when actual conflict arises and must be resolved. Interjurisdictional immunity, by contrast, may thwart such productive cooperation.”

Despite how the pundits are trying to frame the issue, this is not primarily a federal-provincial dispute. The most important legal conundrum of the Kinder Morgan struggle is how Aboriginal rights and title (or jurisdiction) provides a check on unilateral federal and provincial powers. No one foreshadowed this better than Green Party leader Andrew Weaver when he suggested, “Notley ought to have a look at section 35 of our Constitution” in response to a question about how the newly announced NDP-Green alliance intended to stop Kinder Morgan. Section 35 recognizes and affirms the Aboriginal and treaty rights of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Section 35 imposes specific obligations on both the provinces and federal governments to engage Aboriginal peoples who will be adversely affected by a proposed government action (for example, an oil port or pipeline).

Section 35 further complicates the balancing of interests the courts will inevitably seek in resolving the jurisdictional issue. Canadian courts have never considered the impact constitutionally protected First Nations title and rights have on the balancing in provincial and federal standoffs. First Nations’ jurisdiction is a true wild card.

While British Columbia’s reference of the jurisdictional issue was a smart move, it might not have maximized the impact of other legal tools, specifically using B.C.’s constitutionally imposed obligations to consult and accommodate First Nations as both a sword and a shield.

Although resetting and transforming the relationship with First Nations is a “foundational piece” of the power sharing agreement between the NDP and Green Party, the government has not kept this commitment at the centre of its responses to Kinder Morgan.

British Columbia’s mixed approach

The appointment of Thomas Berger to represent British Columbia as outside counsel on Kinder Morgan was applauded, but many of the subsequent choices have been ill considered. B.C.’s most egregious misstep was the decision to stand behind the evidence introduced by the previous Christy Clark government in the Squamish Nation’s challenge of the province’s Kinder Morgan approval. Ironically, while it is fighting off the big bad wolves from the other side of the Rockies, in the B.C. Supreme Court Horgan’s government defended the conclusion of the Clark government that Kinder Morgan would not have significant environmental impacts and that obligations to the Squamish had been fulfilled. Horgan’s government defended Clark’s approval despite knowing there were bureaucrats who were pulled off the Kinder Morgan file by the Clark government because they objected to the way First Nation and Squamish concerns were being ignored.

Berger could have easily gathered this evidence and filed it in the Squamish case. An affidavit from one of these government officials attesting to the inadequacies of Clark’s approval would have gone a long way to helping the Squamish quash Kinder Morgan’s environmental certificate, thus killing the proposal. Instead Horgan’s government decided to defend Clark’s approval, arguing it was obligated to because constitutional convention and the “honour of the Crown demands that B.C. defend its actions.” Filing a revised factual record that more accurately reflects what happened would uphold the Crown’s honour, not undermine it.

The B.C. government also seems to have lost sight of resetting the relationship with First Nations when reviewing the 1,187 provincial permits Kinder Morgan requires. It has committed to reviewing and reconciling laws and policies with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Supreme Court’s Tsilhqot’in decision. This is no easy task; it will take time.

In the meantime, the government could implement the spirit and intent of its commitment in the power sharing agreement by instructing the staff reviewing Kinder Morgan’s permits to bend over backwards to engage affected First Nations on any issue, even if they tangentially involved. This doesn’t appear to have happened.

The controversy around Kinder Morgan is unlikely to go away anytime soon. While it roils, it is taking up a lot of political bandwidth in Victoria and Ottawa while distracting from other important work.

It is in the British Columbia government’s interest to make it go away as quickly as possible. So, while Horgan’s government has used most of the tools available to it, it has not always deployed them as effectively as possible.

As the battle heats up, B.C. must up its game considerably, particularly in using its commitment to transform relations with First Nations not just as a shield, but also as a sword.

Failure is not an option on this file. The consequences of messing up, both for the future of our magnificent coast, and for the NDP’s prospects of remaining government, couldn’t be more connected.